Quantitative Tightening, Volatility, and Considerations for Funding

At the October Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) meeting, the FOMC statement indicated that reduction of the Fed’s balance sheet will end December 1, 2025, earlier than many in the market expected. The end of Quantitative Tightening may have implications for interest-rate volatility. FHLBank Boston offers advances with embedded options, like the HLB-Option and Member-Option Advance, for navigating interest-rate changes.

What is Quantitative Tightening (QT)?

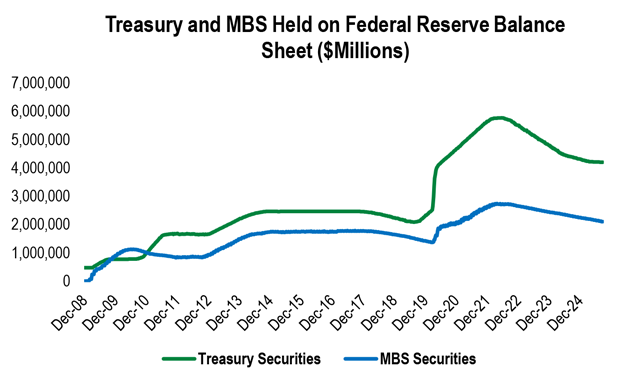

The Federal Reserve (Fed) purchased large quantities of financial assets, including Treasury and mortgage-backed securities (MBS), as part of its response to the Great Financial Crisis in 2008 and the recession caused by the COVID-19 epidemic in 2020. These asset purchases, known as Quantitative Easing (QE), were intended to stabilize market function and support lending. In the past 20 years, there have been four instances of QE – three after the Great Financial Crisis and one during COVID.

Despite the relative frequency of these purchases, the Fed considers asset purchases a nontraditional policy and has indicated that, in the long term, it seeks to maintain a balance sheet smaller than the current one, relative to GDP, and composed primarily of shorter duration Treasury securities.

To achieve the dual goals of reducing the Fed’s overall footprint and shifting the composition of the balance sheet to primarily Treasury securities, the Fed has twice implemented Quantitative Tightening (QT). In QT, the Fed reinvests principal payments that exceed predetermined “caps,” so that the overall size of the balance sheet is reduced over time.

As shown in the graph below, assets on the Fed’s balance sheet peaked at about $8.9 trillion in 2022. After a ramp-up period, the Fed then began running off the balance sheet by reinvesting principal payments that exceeded the “caps” of $60 billion per month for Treasurys and $35 billion per month for MBS. In recent months, the Fed reduced the “cap” for Treasury securities as repo rates moved up and use of the Fed’s standing repo facility increased. Additionally, the Fed began reinvesting principal payments from agency debt and agency MBS securities into Treasury securities, as part of its longer-term objective to move to a portfolio comprised primarily of Treasury securities.

Quantitative Tightening to End in December 2025

Since the growth of the Fed’s balance sheet began, the Fed has implemented monetary policy using a “corridor system.” In this system, short-term rates controlled by the Fed, including interest on reserve balances (IORB) and the overnight reverse repo rate (ON RRP), are important tools for keeping the effective federal funds rate, which is the rate formally targeted by the FOMC, in the target range. The corridor system works when reserves are sufficient to predictably contain the effective federal funds rate. When reserves become too scarce, excess demand from banks may push the effective fed funds rate out of the target range.

The Fed has undertaken efforts to reduce the balance sheet but cannot reduce it to levels observed before the Great Financial Crisis, when the monetary policy implementation framework worked somewhat differently. The Fed has described the evolution of the balance sheet as moving from “abundant” to “ample” reserves, as QT reduces the Fed’s overall footprint. In recent months, repo rates have increased, and the effective federal funds rate has moved up relative to IORB, both of which suggested the level of reserves was nearing “ample.”

At the October FOMC meeting, the Statement indicated that balance sheet reduction will conclude December 1, 2025. This was earlier than many market participants expected. Results from the most recent New York Fed’s Survey of Market Expectations indicated that the median respondent expected QT to end in early 2026.

| Period in which SOMA Portfolio Ceases to Decline | Size of SOMA Portfolio When it Ceases to Decline ($Billions) | |

| 25th Percentile | January 2026 | 6,188 |

| Median | January 2026 | 6,188 |

| 75th Percentile | April 2026 | 6,188 |

| Respondents | 46 | 47 |

What are the Relative impacts on MBS and Treasury Purchases?

As of the beginning of October 2025, the Fed held about $4.2 trillion in Treasury securities and $2.1 trillion in MBS. The Fed reduced its Treasury holdings at a faster pace than its MBS holdings for the following reasons:

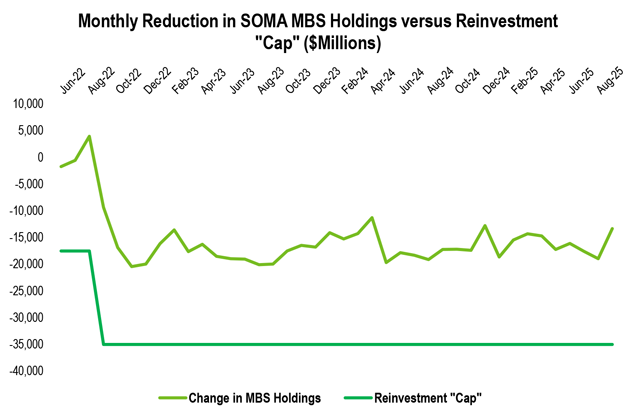

- The Fed’s peak reinvestment cap on Treasury securities of $60B/month was higher than the cap for MBS of $35B/month.

- Unlike Treasury holdings, the Fed’s MBS securities are not maturing at a pace that allows the Fed to reach the $35B/month MBS reinvestment cap. Recall that the Fed bought MBS in the aftermath of 2008 and during the COVID epidemic. At those times, interest rates and mortgage rates were significantly lower than they are today. As a result, the Fed primarily holds MBS with coupons well below the prevailing coupons on newly issued MBS. As mortgage lenders know well, these lower-rate mortgages have extended in duration, are not prepaying at historically normal rates, and are unlikely to prepay soon. In practice, the Fed has reduced its MBS holdings at a pace of about $20B/month, lower than the cap would allow if prepayments were higher.

In recent months, the Fed has been reinvesting principal payments on agency debt and agency MBS that exceed the cap into Treasury securities. At the October meeting, the FOMC indicated that after December 1, all principal payments from the Federal Reserve’s holdings of agency securities will be reinvested into Treasury bills. This will further the FOMC’s goal of holding a balance sheet primarily of Treasury securities over time.

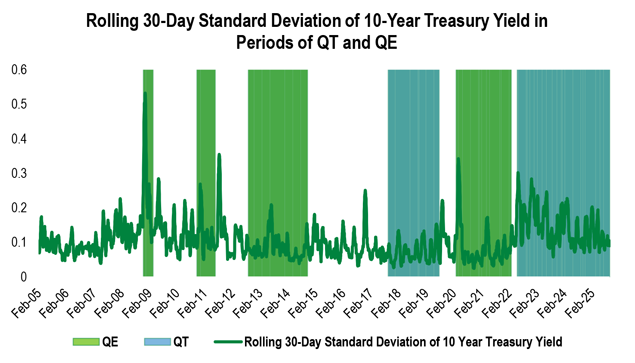

Quantitative Tightening and Interest-Rate Volatility

It is important to have humility whenever one makes quantitative claims about QE and QT. Both strategies are relatively new in economic terms and tend to occur in periods of material economic turbulence. In theory, interest-rate volatility should be lower in periods of QE because the introduction of an incremental buyer in the Fed depresses the term premium. The opposite should be true in periods of QT, when all else is equal, the incremental buyer is removed. Indeed, in practice, average interest-rate volatility is lower in periods of QE than QT. While we cannot confidently draw any statistically significant causal relationship, it is worth considering the possibility that changes in the Fed’s balance sheet policy will have implications for interest-rate volatility.

FHLBank Boston offers advances with embedded options. Generally, if a member expects volatility to increase, it may be appropriate to buy an option. However, if a member expects volatility to decline, it may be appropriate to sell an option.

Interest-rate volatility has implications for depositories for three reasons. First, higher interest-rate volatility has implications for prepayment of securitized assets, including mortgages. Second, higher interest-rate volatility makes interest-rate risk management more challenging. And finally, if a depository has a strong view on the likely direction of interest-rate volatility, it may be appropriate to buy or sell options in the depository’s funding source.

Advances for Navigating Volatility

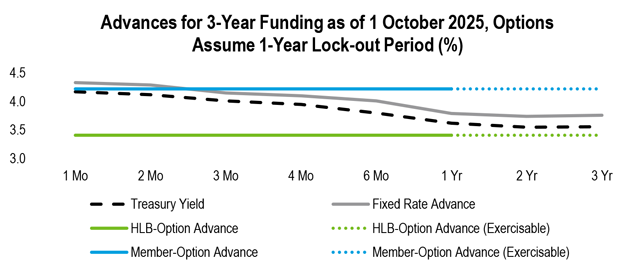

FHLBank Boston offers advances with embedded options. Generally, if a member expects volatility to increase, it may be appropriate to buy an option. However, if a member expects volatility to decline, it may be appropriate to sell an option.

The advances with embedded options offered by the Bank are customizable. Typically, the member and FHLBank Boston agree to a “lockout” period in which the option cannot be exercised, and the agreed-upon funding rate is guaranteed. After that lockout period, whichever party holds the option can exercise it until the advance matures.

If a member expects volatility to decline, they might consider an HLB-Option Advance. With the HLB-Option Advance, FHLBank Boston has the option to end the advance at the conclusion of the lockout period. FHLBank Boston will typically exercise this option if interest rates increase. Because FHLBank Boston holds the option, the rate on an HLB-Option Advance generally is lower than a Classic Advance for the same term. Again, though, it’s important to understand that funding is only secured for the lockout period, not the entirety of the term of the advance.

If a member expects volatility to increase, they might consider a Member-Option Advance. A Member-Option Advance allows the member, rather than FHLBank Boston, to hold the option. After the lockout period, the member has the right to exercise their option to close the advance. Typically, a member will be incentivized to do so if interest rates decline. Because the member holds the option, the rate on a Member-Option Advance is typically higher than a fixed-rate advance of the same term.

Caroline Casavant

Caroline helps members understand how economic and financial developments may affect their balance sheet risks and determine how FHLBank Boston can partner with them to manage those risks. Please contact me at 617-292-9735 or caroline.casavant@fhlbboston.com or reach out to your relationship manager for more details.

FHLBank Boston does not act as a financial advisor, and members should independently evaluate the suitability and risks of all advances. The content of this article is provided free of charge and is intended for general informational purposes only. FHLBank Boston does not guarantee the accuracy of third-party information displayed in this article, the views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the view of FHLBank Boston or its management, and members should independently evaluate the suitability and risks of all advances.

Forward-looking statements: This article uses forward-looking statements within the meaning of the “safe harbor” provisions of the Private Securities Litigation Reform Act of 1995 and is based on our expectations as of the date hereof. All statements, other than statements of historical fact, are “forward-looking statements,” including any statements of the plans, strategies, and objectives for future operations; any statement of belief; and any statements of assumptions underlying any of the foregoing. The words “expects”, “may”, “likely”, “continue”, “possible”, “to be”, “will,” and similar statements and their negative forms may be used in this article to identify some, but not all, of such forward-looking statements. The Bank cautions that, by their nature, forward-looking statements involve risks and uncertainties, including, but not limited to, the uncertainty relating to the timing and extent of FOMC market actions and communications and economic conditions (including effects on, among other things, interest rates and yield curves). The Bank reserves the right to change its plans for any programs for any reason, including but not limited to legislative or regulatory changes, changes in membership, or changes at the discretion of the board of directors. Accordingly, the Bank cautions that actual results could differ materially from those expressed or implied in these forward-looking statements, and you are cautioned not to place undue reliance on such statements. The Bank does not undertake to update any forward-looking statement herein, or that may be made from time to time on behalf of the Bank.